The Comic Book Industry: Creator Rights or Wrongs? by Jerry Whitworth

The American comic book industry was largely built from anti-Semitism. The United States (the Americas in general) started from one people imposing their will on other people, Europeans came to the Western hemisphere’s prominent continents and claimed the land therein for their native nations, often pushing out or killing natives that opposed them. This continued on throughout its history, with the prevalence of slavery and minority rights that have since legally made those of different skin color equal but the struggle remains today between people and their differences (skin color, religion, sexual-orientation, economic class, etc). A hatred that continues to fester today is that against the Jews, a hatred since ancient times when the Egyptians held them as slaves and later when Europeans saw them as unscrupulous money lenders and Christians and Muslims held their own special contempt for them. The United States of America, founded as an independent nation with the freedom to practice whatever religion you believed in, made it illegal to hate someone for having different beliefs, but that didn’t stop people from discriminating despite this fact. Jews, regardless of their skill or ability, were often the target of being blacklisted from work. It was often the case you would have a Jewish businessman hire almost exclusively Jewish workers, under the idea of looking out for their own people, but likely more prevalent with a knowledge it would mean cheap labor. Jewish publishers like Maxwell Charles Gaines, better known as M.C. Gaines (formerly Max Ginzberg), Martin Goodman, and Harry Donenfeld founded companies like All-American Publications, Timely Comics, and National Periodical Publications, respectively. Donenfeld, a salesman turned printer, founded National with Jack Liebowitz and was compared to a gangster in Gerard Jones’ Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book (2005) for his aggressive approach to business, promising clients the world and bullying his employees to get what he wanted.

The burgeoning comic book industry was built on the backs of Jews like Joe Simon (born Hymie Simon), Jack Kirby (or Jacob Kurtzberg), Will Eisner, Bob Kane (Robert Kahn), Bill Finger, Jerry Robinson (Sherrill Robinson), Martin Nodell, Joe Kubert, Harvey Kurtzman, Julius Schwartz, Stan Lee (Stanley Lieber), Mort Weisinger, Gil Kane (Eli Katz), Robert Crumb (better known as R. Crumb), Harvey Pekar, Art Spiegelman, Marv Wolfman, and Chris Claremont gave rise to an industry that today inspires film and television and more than a few American icons, often inspired by pulp magazines, radio serials, Science Fiction magazines, and comic strips (the film industry would undergo a similar birth). The most famous of these Jewish creators would be Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, whose creation Superman started the superhero industry and whose presence inspired the American comic book as it is today. However, the pair largely lived as beggars, despite their contribution, to their deaths. For Superman, the pair were paid $130 by National and lost any claim to their creation. In the 1940s, the pair sued National for their creation near the end of their ten year contract to produce Superman stories only to settle out of court for $94,000 under the provision the initial payment for Superman denoted ownership of the creation to National (their names would then be removed from Superman’s credits). By the 1950s, Shuster had to resort to drawing fetish sadomasochistic comic art to make ends meet while Siegel continued to work in the trenches as a comic writer. It wouldn’t be until the 1970s that, with the support of the legendary Neal Adams and an upcoming film adaptation of Superman, that the estate of Siegel and Shuster be awarded an annual stipend of $20,000, health benefits, and their names reattached to Superman as his creators across all media platforms. After the deaths of Siegel and Shuster, their families would again pick up the fight for the rights to Superman (as well as Superboy) which continues to this day (though it would seem some arrangement has been made regarding Superboy).

A dispute of an entirely different nature arose with Batman. Bob Kane made an agreement with National for his Batman creation that had his name attached with a sole creator credit (even if National provided their own artists) as well as payment for ongoing use of his character. However, debate would later rise as to how much involvement Kane even had in the creation of Batman. Notorious for using ghost writers and artists, Kane employed a young Bill Finger for fleshing out the Batman character and Finger claims to have conceived of most of the Dark Knight’s appearance, his real name, and wrote the script for his first appearance (recently, evidence has arisen Kane traced the art he used for his early Batman work from comic strips like Flash Gordon and modified the plots of pulp stories like the Shadow). Beyond this, creations like Robin and the Joker are credited to Kane, but Finger and artist Jerry Robinson claim to have had a little more than a hand to do with their inception (or in the case of the Joker, Finger and Robinson claim sole creation). Finger and Robinson worked for hire, making payment as ghost writers and signing away any rights under their contract with Kane. And yet, after decades of hearing Kane loudly proclaim being Batman and his mythology’s creator, Kane’s ghosts finally began admitting their involvement (which Kane has generally denied). So, there’s no debate regarding money go to men like Finger and Robinson, both of whom and Kane have since passed on, fans to this day decry Kane’s sole claim of creation.

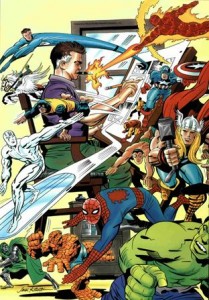

A debate from the Silver Age involves Stan Lee and his development of the Marvel Method of producing comics. When Lee’s co-creations like Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, and the Hulk became too much for him to keep up with, a method was devised to make the creative process more expedited. Called the Marvel Method, Lee would offer some plot for an issue (sometimes a fully developed concept, other times a rough idea), his artist would interpret how to make it happen visually, and Lee would come in and add dialogue. However, just offering a plot generally offered little in the interaction of characters, of the growth of characters, or the thoughts and feelings of characters, thus placing most of the effort on the artists with Lee touching up afterward and taking half (or more) of the credit. Frequent Lee artist Jack Kirby, however, chose to largely remain in the shadows as Lee became a celebrity, working out various deals with Marvel (formerly Timely, Lee getting work as the publisher’s wife’s cousin) that have made him extremely wealthy and famous. Kirby would at times be quite angry with Lee (modeling the villainous con man Funky Flashman after his former collaborator) but never felt he could win co-credit for the works he did with Lee and earn residuals like reprints and adaptations as Lee had. Instead, he was supported by Neal Adams to reclaim some of his art from Marvel (a fight Kirby felt he could actually win) and managed to obtain some creator co-credits. Recently, more than a decade after Kirby’s death, his estate has raised a lawsuit against Marvel, who has been making millions over adapting many of Kirby’s co-creations to film and television. At this time, judgment has been in Marvel’s favor but his estate has appealed.

With the issue of credit and royalties brought up by the likes of Neal Adams and Bill Mantlo, Jenette Kahn, Paul Levitz, and Dick Giordano began a program at DC Comics in the 1980s offering royalties to creators rather than the work-for-hire model from the 1930s they employed up to that point. However, this hasn’t saved the company from controversy. Around this time, Alan Moore went from a critically acclaimed up-and-comer from England coming off of runs on Marvelman and his original series V for Vendetta to work on DC Comics’ Swamp Thing while contributing notable stories to Superman, Batman, and the Green Lantern Corps. DC agreed to release Moore’s V for Vendetta internationally if he agreed to license it to the company with its complete ownership going back to him after being out of print for at least a year. He made a similar deal when he created the series Watchmen with the company using pastiches of DC’s recently acquired Charlton Comics properties. While Moore has since made royalties from these properties, they proved so popular that they have yet to go out of print nearly thirty years later, with film adaptations made of both (and an upcoming series of prequel comic series to Watchmen against Moore’s wishes). The experience left a bad taste in Moore’s mouth and he swore off DC (and Marvel, seeing it as the same kind of animal) but worked quite a bit for Image Comics. So much so, Moore established his own imprint at Image, America’s Best Comics (ABC) under Jim Lee’s WildStorm branch. However, despite the freedom Image awards creators under them, both creatively and permitting all rights to remain with the creator, DC Comics would absorb WildStorm thus placing Moore under their rule again. He would again butt heads with DC, as the company created a live action film adaptation of his book League of Extraordinary Gentlemen against his wishes and pulped already published copies of the same comic series over supposed content issues (leading Moore to take the series to Top Shelf and Knockabout Comics). DC would run into other issues with the supposed freedom WildStorm was suppose to provide such as the adult content of Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson’s The Boys series (which moved to Dynamite Entertainment in response).

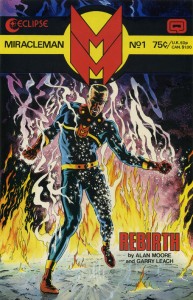

An interesting case of creator rights, which also includes Alan Moore, is that of Marvelman. Superman was a huge hit for National when he was created, as has been discussed. Fawcett Comics created a similar character named Captain Marvel (which DC would eventually sue over shutting down Fawcett and buying Marvel for themselves) which became more popular than Superman. When Captain Marvel was discontinued due to DC’s efforts, Len Miller had British comic creator Mick Anglo create Marvelman to fill the vacuum for the hot property for the United Kingdom. In the early 1980s, Marvelman was resurrected in Dez Skinn’s anthology comic Warrior under Alan Moore, Garry Leach, and Alan Davis and was a huge hit. The series would be licensed to be published in America but, under threat of lawsuit from Marvel Comics, was renamed Miracleman and was also a hit in the states (which greased the wheels for the so-called British Invasion of American comics). Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham would later pick up the book. With the success of Miracleman, there was a scramble to reprint issues and generate new content the issue of ownership arose, as there was a mystery on who owned what exactly with virtually everyone involved apparently owning a portion of the character from Anglo to Gaiman and everyone in between. Todd McFarlane of Spawn fame thought he bought the property for $40,000 as part of purchasing American comic publisher Eclipse Comics (who printed the American comic) but apparently only bought a chunk of it (the part Eclipse owned). Neil Gaiman would form a company called Marvels and Miracles LLC to clear up the issue of rights and buy the franchise himself. Ultimately, Marvel Comics would buy Anglo’s portion of the character (reprinting the early work of Anglo’s stories) and has been trying to clear up the quagmire of the Warrior years and on.

Gary Friedrich

The most recent, pressing issue of creator rights has erupted recently in the case of Gary Friedrich. Claiming to have co-created the Marvel Comics property Ghost Rider, Friedrich used the character’s likeness for years on merchandise to sell and sign at conventions to earn a living. It’s a common practice for comic creators to publish prints of their work or sketches of comic characters at conventions in artist’s alley (or, more recently, off websites) to either supplement their income or, in the case of older creators, to simply earn enough money to continue living off an industry that has largely abandoned them. However, with Ghost Rider spawning two live action film adaptations, Friedrich sued for making some piece of the millions of dollars being made off something he co-created. In response, claims have arisen Friedrich wasn’t even involved in creating the character (with Roy Thomas and Mike Ploog purported as sole creators) and Marvel counter-suing Friedrich for the money he made off printing materials displaying Ghost Rider. Worst still, a trend has started preventing people from selling anything with franchise characters without a license, in essence meaning unless someone owns a character outright or pays some fee can’t produce work like sketches with characters from companies like DC or Marvel. While only a handful of conventions have only recently started doing this, its curious what this trend means for conventions (many fans going to them for sketches) or comic creators’ ability to make a living off their industry (which generates most of its money from licensing such as in merchandise and film and television adaptations).

In the case of something like Malibu Comics, which was fairly popular (spawning the animated series Ultraforce) and was bought by Marvel, who hasn’t utilized the purchase according to rumor because royalties would be owned to the Malibu creators, or DC Comics who published a mostly-creator owned imprint like Milestone Media (which spawned the animated series Static Shock) only to later enter a partnership that saw the imprint merged with DC and characters like Icon and Rocket animated into Young Justice (or with the deal Tony Isabella had between DC and his creation Black Lightning where he earns royalties from his use), some middle ground needs to be found. Perhaps companies like Image or Dark Horse, who offers a platform for creators to get their work out there for a fee, can be some model to follow but still, if you consider Image and Dark Horse combined only control some less than ten percent of the comic book industry at any given time while DC and Marvel combined have around eighty percent, the latter seems better for exposure. Something needs to be done, but I’m not sure anyone knows what that is.

http://www.newsarama.com/comics/the-q-creators-on-comic-book-lawsuits.html

And what about Steve Ditko’s NO credit! For especially co-creating Spider-Man!